Fr: bleuet fausse-myrtille, airelle faux-myrtille, bleuet du Canada, bleuet rameau-velouté

IA: inniminanakashi

Ericaceae - Heath Family

Note: Numbers provided in square brackets in the text refer to the image presented above; image numbers are displayed to the lower left of each image.

General: An erect to spreading, low deciduous shrub [1–2], 2–6 dm tall (rarely taller in the north); plants have a deep extensive taproot system and rhizomes capable of forming clones (Vander Kloet and Hall 1981). Velvetleaf blueberries are an important food source for a variety of birds and mammals, including bears; ruffed grouse are known to eat flower buds during winter months, but leaves are not often eaten as browse (Tirmentein 1990).

Key Features:

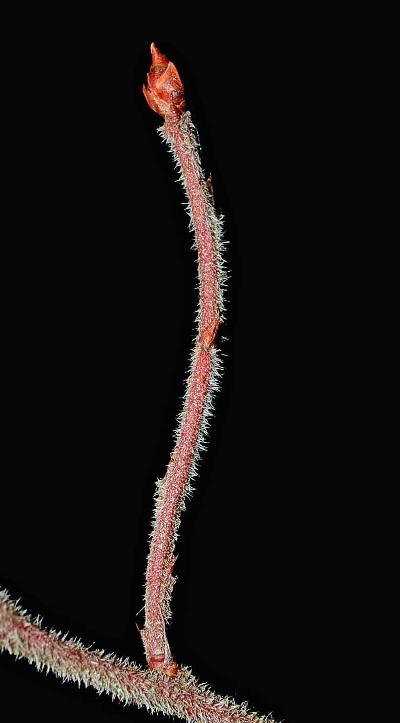

1. Stems are green when young, reddish-purple at maturity, with a dense coat of short white velvety (pilose) hairs [3–4].

2. Leaves are alternate, elliptic, and velvety pubescent, especially on the lower surface [5–6].

3. Flowers are borne in terminal racemes of several flowers [7], followed by blue berries with a glaucous bloom [8].

Stems/twigs: Young twigs are terete, green, and softly pubescent [9], becoming reddish with maturity; the surface is finely warty (verrucose) and covered with short stiff white hairs (pilose-hirsute) [3–4]. Once the pubescent outer bark is shed, mature stems have reddish-brown to dark brown bark. Flower buds, located at the stem tips, are ovoid, blunt (obtuse), and larger than the lateral vegetative buds [4]; lateral buds are alternate, small, dark reddish-purple, lanceolate, scaly, with two very slender outer bracts that persist at the base of older twigs [4]. Leaf scars are small and narrowly hemispherical, with a single bundle trace scar, although usually not visible due to the hairiness of the stems.

Leaves: Alternate, simple, pinnately-veined, and with short pubescent petioles. Leaf blade are elliptic to lanceolate, bases are tapering (cuneate), the apex is pointed (acute), and margins are entire and hairy [9–10]. Young leaves are reddish-bronze as they expand [11], while mature leaves are dark green above, usually 2–4 cm long by about 1–1.5 cm wide, and short pubescent [9–10]; the lower surface is downy pubescent [13], either persistently so, or becoming glabrous except along the veins. Leaves turn reddish-orange to dark reddish-purple in autumn [14].

Flowers: Bisexual, in tight terminal inflorescences (racemes), with several flowers on short pedicels [15, 7], which elongate as the flower matures. The green calyx has 5 triangular lobes; the corolla is white to tinged with pink, especially when young, 3–5 mm long, and urn-shaped (urceolate), with 5 short reflexed corolla lobes at the tip [16–17]. The 10 stamens have filaments that are usually hairy and anthers that end in elongate tubular pores; the single pistil has an inferior ovary, a long slender style surrounded at the base by a nectar disk, and a small capitate stigma. The nectar of velvetleaf blueberries reportedly has a higher sucrose content than nectar of lowbush blueberries (Tirmentein 1990). As in lowbush blueberry, pollination of velvetleaf blueberry is primarily by bees (melittophily), which use buzz pollination to effectively pollinate the flowers (Buchmann 1983). However, andrenid bees (Andrena spp.) are the primary pollinator, as they are better able to manipulate the small corolla than bumblebees, who also visit this blueberry (Vander Kloet and Hall 1981). Honeybees and other smaller bees do not sonicate, so cannot effectively pollinate blueberry flowers. Flowers bloom in mid to late spring.

Fruit: In clusters of few to several globose dark blue berries, 6–10 mm in diameter, usually with a pale glaucous bloom that rubs off easily [18–22]. The persistent calyx lobes form a short 5-pointed crown at the top of each berry [23–24]. Technically, the fruit is a false berry, since the ovary is inferior and adnate to the hypanthium tube; true berries are derived from superior ovaries, with only the ovary developing into a fleshy berry. Velvetleaf blueberries are edible, with sweet flesh and about 10–40 small seeds; the berries may be used in similar ways to those of lowbush blueberries. Fruits mature in late summer to fall and are dispersed primarily by mammals and birds (endozoochory).

Ecology and Habitat: Little is known about the ecology of velvetleaf blueberry in Newfoundland and Labrador, since it is known only from limited collections in central and western Labrador. It is not recorded in any of the published vegetation classifications for our region. Vander Kloet and Hall (1981) describe the habitat from across its range as "Disturbed sites in boreal forest, muskegs, bogs, barrens, headlands, outcrops, and mountain meadows."

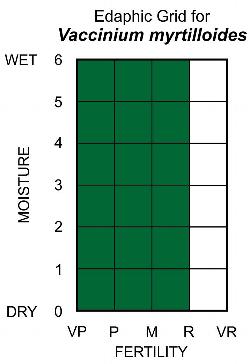

Edaphic Grid: See image [25]: the Edaphic Grid for Vaccinium myrtilloides (based on observations within Québec).

Forest Types: Velvetleaf blueberry has not been recorded in any of the existing vegetation classifications in Newfoundland and Labrador. Within the Québec forest classification, it occurs most frequently (26–50%) in the edaphic grid position of mesic, and sporadically on medium to very poor, across dry to wet moisture regimes (Blouin and Berger 2004).

Succession: Velvetleaf blueberry responds rapidly to disturbance by fire and cutting, and dominates in early successional stages. It is a dominant species of balsam fir-red spruce cutovers in eastern mainland Canada (Vander Kloet and Hall 1981) where, on burned sites, a Wintergreen-Canada beadruby-Velvetleaf blueberry-Bunchberry Association commonly develops under a regime of frequent light fires. However, a Bunchberry-Velvetleaf blueberry-Kalmia-Bracken fern Association is more typical, where fire intervals are longer and fires more severe. Velvetleaf blueberries can persist in closed forests, but flowering and fruiting is typically much reduced or absent in dense shade in all community types (Tirmentein 1990).

Distribution: Velvetleaf blueberry is a transcontinental boreal species that occurs in all Canadian Provinces except Nunavut and the Yukon. It is absent from insular Newfoundland, but occurs in southern, central, and western Labrador (Vander Kloet and Hall 1981), although reports of Vaccinium myrtilloides from Rigolet (54°11' N; CAN, GH) by Scoggan (1979) have been referred to Vaccinium angustifolium (Meades et al. 2015). In the United States, velvetleaf blueberry primarily ranges west from Maine to Minnesota and southeast along the Appalachians to North Carolina; in the western States, it also occurs in small portions of Montana and Washington States (USDA, NRCS 2016).

Similar Species: Where their ranges overlap in Labrador, velvetleaf blueberry and lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium Aiton) often grow together in the same habitat, but lowbush blueberry can be recognized by its glabrous leaves with finely serrulate margins and glabrous warty twigs. Northern blueberry (Vaccinium boreale I.V.Hall and Aalders) is a low shrub similar to lowbush blueberry, also glabrous, but less than 1 dm tall. Northern blueberry leaves and fruit are also smaller than those of lowbush or velvetleaf blueberry, with leaves only 21 mm long by up to 6 mm wide and glaucous blueberries 3–5 mm in diameter.